AI religion is here, and some sects are happier about it than others.

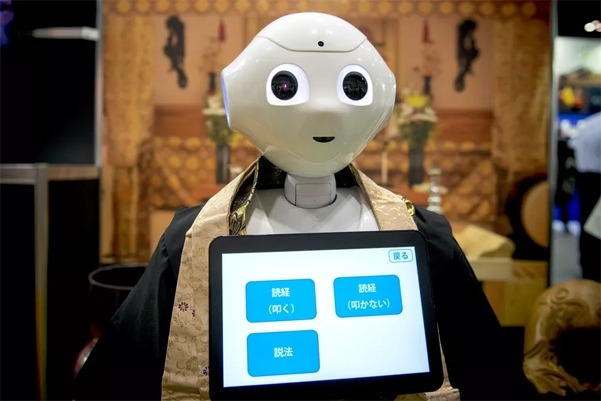

Another cog has been added to the mechanics of faith (so to speak) as the automation of society has spread to the temple and pew of religion. Increasingly, robots have begun to crop up in places of worship to stand in for priests and other religious officiators. In various countries around the world it is now possible to be advised, blessed, and even have your funeral performed by a robot.

And it’s a safe to say there’s feathers a-wrustlin’.

The use of AI in places of worship has unsurprisingly evaded Western and Abrahamic religions up until now. You’re more likely to find robo-priests cropping up in Japan or India, where prevailing religions have softer rules on idol worship. A new priest made of aluminium and silicone named Mindar has begun holding ‘forth’ (a Buddhist worship ceremony) at Kodaiji, a 400-year-old temple in Kyoto, Japan. Check him out in the video above.

Designed to look like Kannon, the Buddhist deity of mercy, Mindar was made to help reignite the people’s passion for their faith in a country where religious affiliation is on the decline. It currently has the capability to recite the same preprogramed sermon about the Heart Sutra over and over – not exactly AI yet so much as just the ‘A’ part. Midar also cost $1 million USD to build.

Still, it looks pretty swanky, and with the integration of AI there’s no doubt a machine like Mindar could be programmed to perform many more functions of religious leaders. The creators say they plan to give Mindar machine-learning capabilities that’ll enable it to tailor feedback to worshippers’ specific spiritual and ethical problems.

Mindar isn’t the only example of this trend. In 2017, Indian scientists created a robot that can perform the Hindu aarti ritual, which involves moving a light around in front of a deity. That same year, Germany Protestant Church created the BlessU-2, a robot that can give out as many as 10,000 blessings and not get tired.