The argument in favour of facial recognition technology

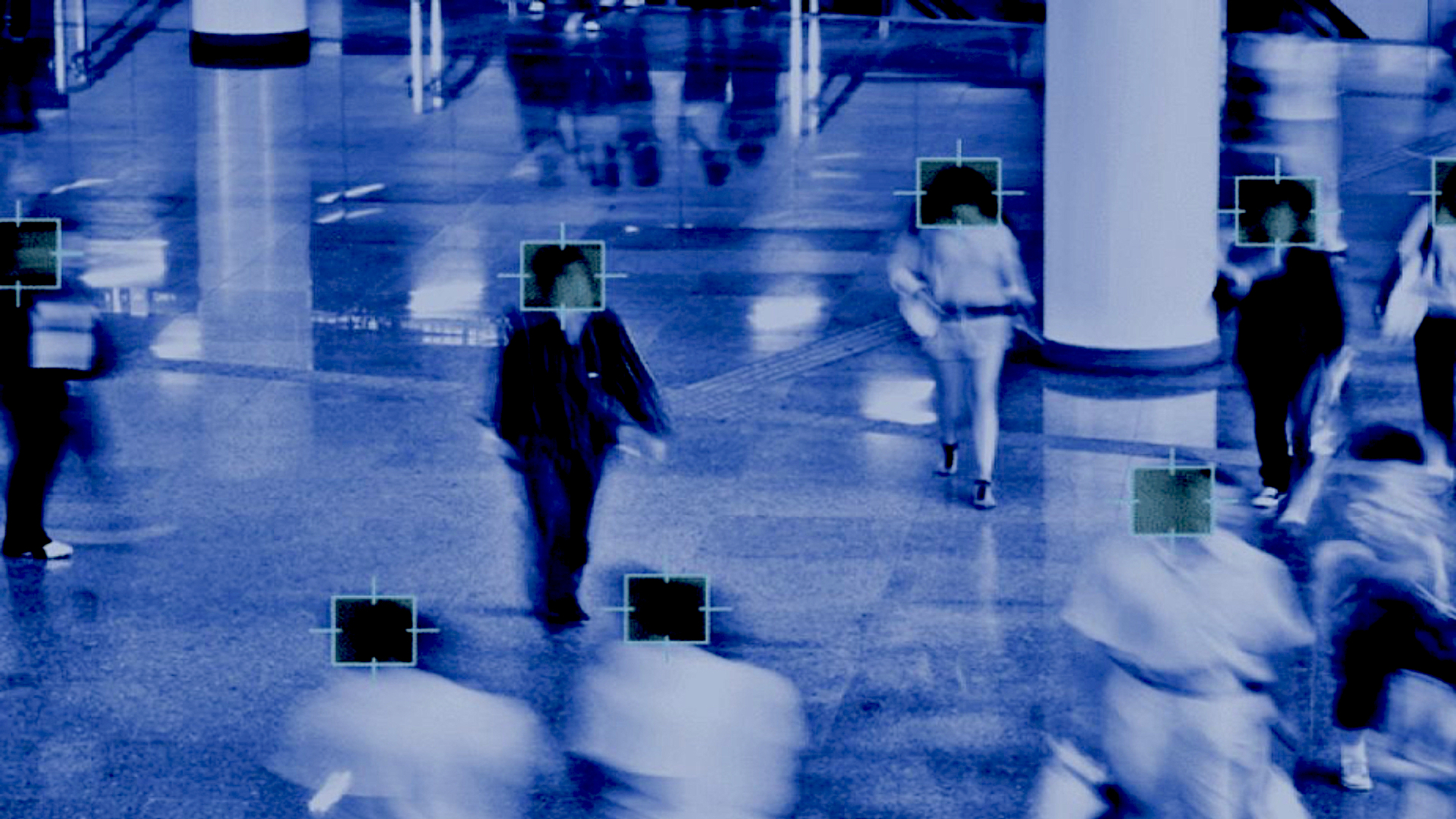

In the interest of public safety, facial recognition technology has been utilised to monitor criminals’ movements for suspicious activity once they are released from incarceration.

It has also been successful in locating missing persons and children, even years after their disappearance with the help of digital ageing software which can predict what they might look like as adults.

But facial recognition technology finds its biggest advocate in identifying suspects who commit crimes in public. This is especially relevant, as over the last 5-10 years, politically motivated violence has increased as polarisation in modern society rises.

Reports show that in the West, 70 violent demonstrations were recorded in 2019 compared to just 19 in 2011. Even in the most surveilled city in the world, some violent offences occurring in the public sphere remain without prosecution – even when video evidence is available.

One example of this is the case of the ‘Putney Pusher’, when in 2017 an indistinguishable jogger pushed an unsuspecting woman in front of a moving bus.

Footage of the incident was caught on CCTV as well as the bus’s onboard cameras and was featured across virtually every news channel in the UK.

Despite these solid pieces of evidence, the man was never identified, leaving motivations for incident and the identity of the perpetrator to become a case for discussion amongst internet sleuths.

Many have suggested that if strong FRT was available at the time, this person could have been caught by police.

Could facial recognition technology become a slippery slope?

For those with concerns over the use of facial recognition, hesitancy doesn’t lie in tracking faces of the public for the practical reasons explored above.

Instead, advisors are concerned that access to a rich database of identities could lead to abuse of power.

A policy advisor at the European Digital Rights advocacy group stated that those in charge with monitoring can ‘in effect turn back the clock to see who you are, where you’ve been, what you have done and with whom, over many months or even years.’

She added that ‘the technology [has potential to] suppress people’s free expression, assembly and ability to live without fear.’

It’s a daunting possibility, for those who feel that they have the right to live their life freely with a high degree of personal privacy.

Who is to say that those with access to databases for facial recognition technology can be trusted not to misuse it to spy on people they know or digitally stalk members of the public?

Indeed, the argument for tracking politically motivated criminals and terrorists seems like a strong one, but data suggests that fear surrounding these events are intensified by over-reporting in the media.

Such events of are disproportionately documented compared to other, more common causes of death such as health complications, homicide, or road accidents. Acknowledging this, some may believe the occasional benefits of facial recognition technology would not outweigh their right to privacy.

A force to be reckoned with

As cities are adapted to become ‘smarter’ in line with the technologies we use in airports and the phones in our pockets, the widespread use of facial recognition technology in public spaces could become the next thing we come to accept as society.

We hardly bat an eyelid anymore when we are presented with targeted ads for a product we briefly discussed with our colleagues or housemates.

It’s safe to say we have accepted that data is constantly being collected on our many behaviours – even if we aren’t really sure how this even works.

But with any new form of technology, pre-empting the dangers behind its widespread use should be considered by the experts.

In a time where it’s never been more evident how authority can lead to abuse of power, the debate over how facial recognition technology is used and how it will be regulated will be crucial in years to come.