Martin Scorsese delivers another magisterial mob epic, this time trading in the avaricious tropes of the ‘wiseguy’ for a reflective and melancholic story to live long in the memory.

The Irishman is likely to be the final chapter to Martin Scorsese’s body of crime movies, and he doesn’t waste a single of its 209 minutes. The key draw here is undoubtedly the swan song performances of a generation of legendary actors, but the weighty script deserves just as much acclaim for allowing everyone to shine in equal measure. Scorsese’s story this time around is a captivating exploration of the passage of time and the roles small men play in the big moments of 20th century history. Think Goodfellas, but with a dourer note. The final act is a humdinger that lingers in the mind long after the credits have rolled too.

Like a fine wine Robert De Niro just seems to get better with age, and at 76 he steps into the shoes of Frank Sheeran; a mild-mannered ex WWII vet who ‘paints houses’ around Philadelphia. To the uninitiated, a house painter in the mob is someone who ties up loose ends (often with a garrotte or a few well-placed bullets, and always a shut mouth). Shining with practiced ease, De Niro carries a stolid apathy and a quiet dignity – two qualities that Frank utilises in equal measure, depending on the job at hand. Schooled in the ethic of following orders from his time in Germany, Frank quickly becomes a vital asset to several big players in Philly’s criminal underworld.

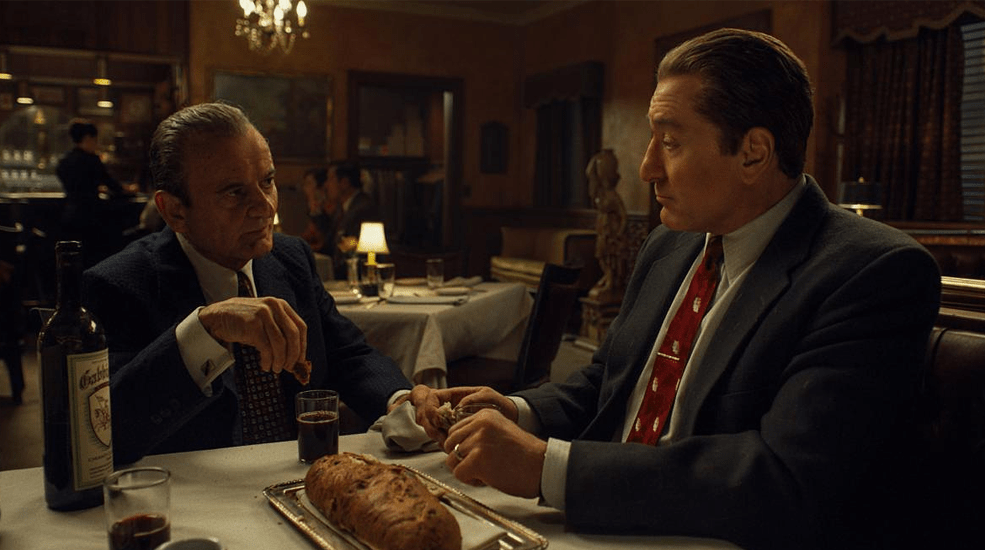

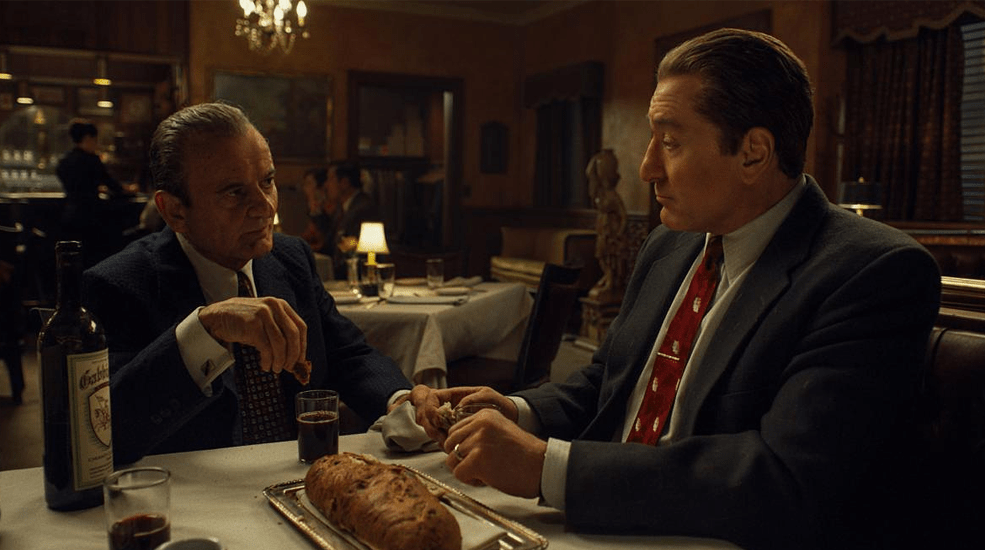

Frank’s endeavours to make a little more than is being offered by his delivery driver jobs eventually leads him to Russell Bufalino (Joe Pesci), a Pennsylvania mafia don who he happens to have met in a chance encounter on the road just a few months before. After rubbing shoulders with a cavalcade of men with leathery faces and averting eyes in dimly lit Italian restaurants, Russell offers Frank a few lucrative jobs and quickly discovers his inherent knack for organised violence. For some time after, hits are carried out, paper packages exchange ring-laden hands, and the disposing of firearms periodically raises the height of the local riverbed, until Frank attracts the attention of new admirer ‘from the top’ who want’s some houses painted.

Played by the third of Scorsese’s galacticos, Jimmy Hoffa (Al Pacino); a crooked yet rousing politician calls on Frank to provide ‘muscle’ while he loans wiseguys cash from the union pension fund, in return taking a hefty slice of the interest rate. The two quickly strike up a great friendship, with the useful Frank assuming the roles of Jimmy’s factotum, bodyguard, consigliere, and occasional pyjama pal – not like that.

For a time, Frank remains equally loyal to both Jimmy and Russell (who have a decent rapport themselves) and often tos and fros between the two attending meetings, lending a droopy ear, and occasionally ridding them of ‘obstacles’ the best way he knows how. All is well for a few years, but predictably, trouble starts to brew as the film nears its breath-taking crescendo, as clashing political agendas bring tensions to a head.

The situation is further exacerbated by President Kennedy’s appointment of brother Bobby as Attorney General; a man with a known zest for pursuing criminal organisations, and incidentally, the corrupt Jimmy. Without spoiling too much, Jimmy’s empire is stripped away from him and his reluctance to take a backseat from public appearances starts to raise concern… ‘concern’ equals crisis in the mafia. After Jimmy makes noises that his mobster debtors are ‘ungrateful’ and suggests he could blow the whistle on them if they threaten his livelihood (or his actual life for that matter), Frank is called upon and asked where his devout loyalty really lies.

It’s worth echoing again that the cast and director were the main draw for anyone who visited the multiplexes or sacrificed a whole evening on Netflix for The Irishman, and not a single performance disappointed. Even Action Bronson’s arbitrary cameo was well acted. In theory the notion of Pesci playing a mentor figure to De Niro is an odd one, but my God does the little man make it work. Coaxed out of retirement by Scorsese, Pesci is an absolute marvel in the role of Russell Bufalino: not scary and hot-headed like Tommy DeSimone, but a quiet schemer, a fixer. In many ways, his control and influence in this orchestrator role makes him even more menacing.

De Niro’s portrayal of Irish hitman Frank Sheeran is as fine a performance as we’ve seen from the man since Casino (1995). His moments of quiet resignation, and muted sadness are absolutely devastating, and sporadic passages of him struggling both physically and emotionally in his twilight years really raise a lump in the throat. The finest performance, for me, came from Al Pacino as the loquacious Jimmer Hoffa though. In a role unlike any I’ve seen from the eight-time Oscar winner, Pacino exudes a brashness and imperviousness to almost everyone (bar his confidant Frank) and his constant quipping provides some of the more memorable lines from the film.