Disrupting global efforts to put an end to FGM practices, deepening poverty caused by the pandemic means more girls are now at risk of being cut.

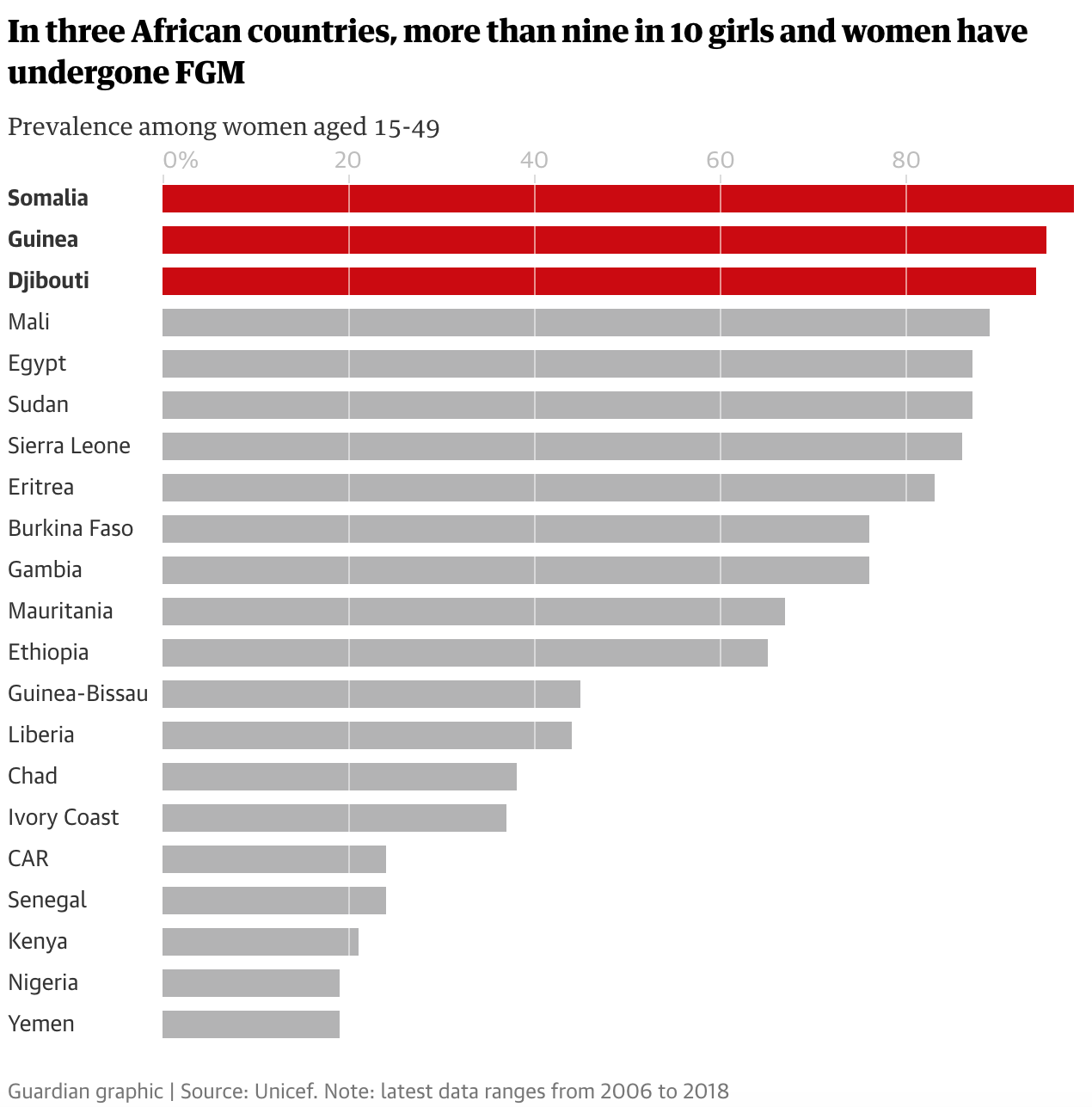

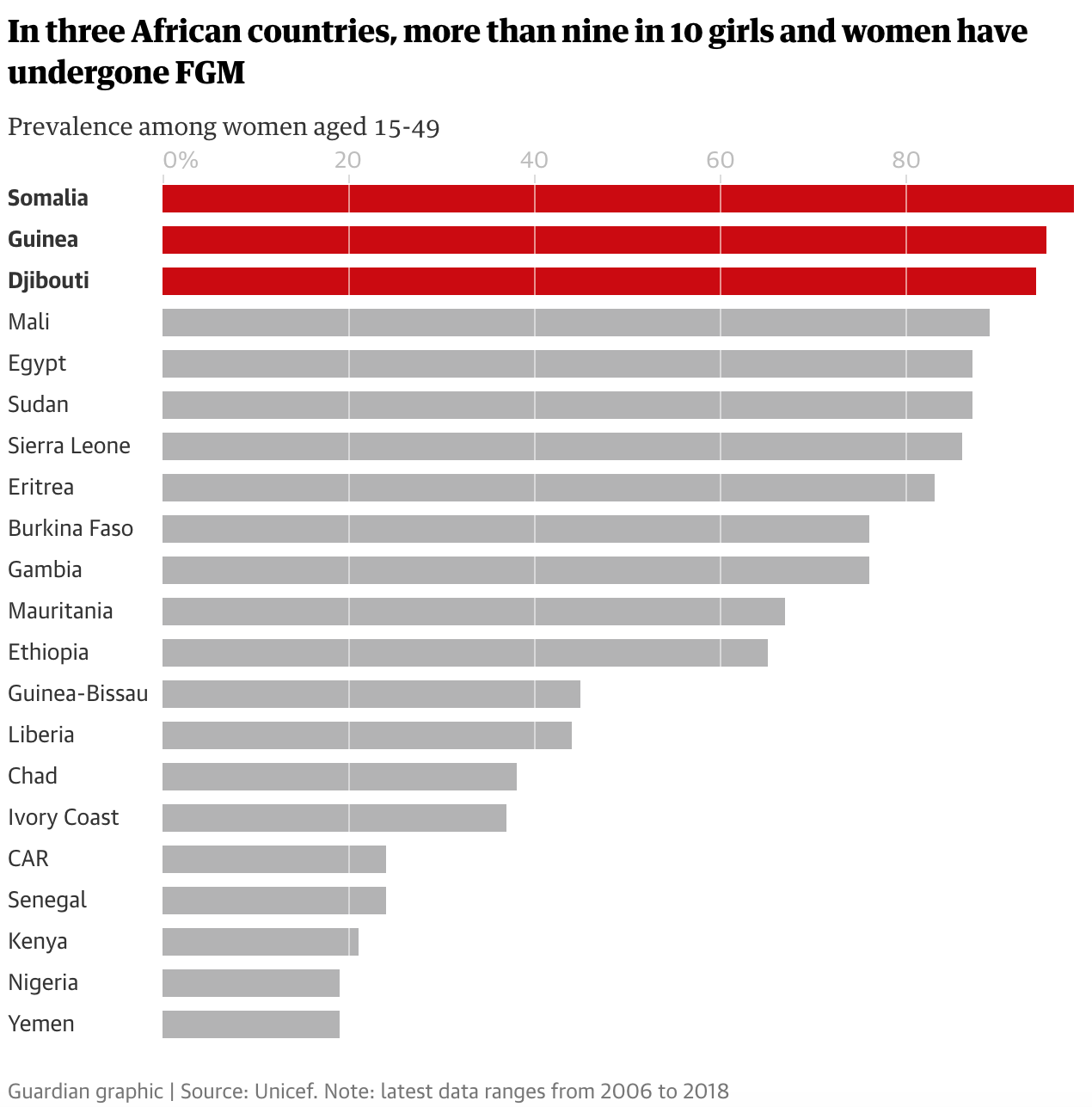

According to a United Nations official, Coronavirus has reversed progress on ending female genital mutilation (FGM). The (almost) universally condemned practice, which affects 200 million girls and women worldwide, involves the partial or total removal of the external genitalia and, in some African countries, the vaginal opening is sewn up too. Traditionally carried out to dictate proof of sexual purity, the procedure is often performed by ‘healers’ or untrained midwives using razors, broken glass, and knives.

Causing lasting harm to female health, education, and future opportunities, these practices are profoundly rooted in gender inequality as well as the male desire to control women’s bodies and, ultimately, their lives.

As a direct result of the pandemic, two million girls could undergo FGM in the next decade, far beyond what would normally be expected. In addition, deepening poverty caused by the crisis has the potential to push more parents into marrying off their young daughters.

It’s a seriously concerning issue that Natalia Kanem, head of the UN’s sexual and reproductive health agency, is referring to as a ‘silent and endemic crisis.’

Unfortunately, those believed to be at risk would have been safe were it not for faltering economies and extended periods of lockdown that have forced school closures. ‘Being in school is the main reason girls don’t get cut,’ says anti-FGM campaigner Domtila Chesang. ‘The girls are safe in school. With the schools closed, there’s no alternative – they are left to the mercy of their parents and communities.’

Restrictions on movement in quarantine have also made it near-impossible to raise awareness about the dangers of FGM within communities. With more girls staying indoors and their parents seeking to achieve financial security by cutting them, activists are understandably deeming the UN’s deadline to end FGM by 2030 extremely unlikely.