Where does all the money go?

In the lead up to COP26, the UK called for high-income countries to deliver on their promise. But this money isn’t only meant for adapting to climate change. Commitments to public finance moving forward must also include building new markets for mitigation and adaptation, and improving access to finance for communities around the world looking to take climate action.

And what does this mean for receiving countries? It means cheap, reliable, and renewable clean electricity for schools in rural Africa, better infrastructure and defences against storm surges for the Pacific islands, improved access to clean water in Southeast Asia, and more.

Is public investment enough?

Not according to Rishi Sunak, finance chancellor of the UK, who acknowledged the need for both public and private finance to ensure that the 1.5 C goal be met. With a need to deploy the investments necessary to combat climate change, countries around the world plan to accelerate three actions.

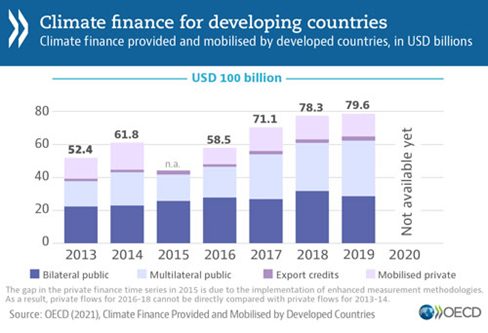

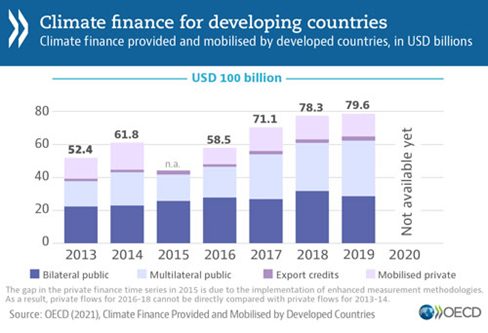

The first is to be an increase in public investment and more collaboration between developed and developing countries, as well as a renewed pledge of $100 billion USD a year by 2025.

The second, mobilising private finance, has already begun to show some progress. Sunak recently announced that the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net-Zero (GFANZ) now consists of over 450 firms representing $130 trillion USD. That’s nearly double the $70 trillion USD when GFANZ was launched in April.

These firms must now commit to using science-backed guidelines to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 and provide 2030 interim goals.

The final action will be rewiring the global financial system for net-zero. This includes things like proper climate risk surveillance, better and more consistent climate data, etc.

But this is all easier said than done. According to United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, ‘there is a deficit of credibility and a surplus of confusion over emissions reductions and net zero targets, with different meanings and different metrics.’

There are also concerns over greenwashing and monitoring which, if not addressed effectively, may lead to more unfulfilled promises.

Many, however, remain hopeful that both private firms and high-income countries will do their part in financing a just and equitable transition to a green world. So as we continue to hear promises, promises, and more promises from leaders at COP26, it is critical that we also continue to demand real action.

This article was guest written by Ghislaine Fandel, the Science Communication Lead & Content Director at ClimateScience. View her LinkedIn here.