Home to over half of the human rights activists murdered in 2020, the country’s president will boost military operations against the criminal groups responsible and send more judges to remote areas.

Last year was the deadliest on record for human rights activists in Colombia.

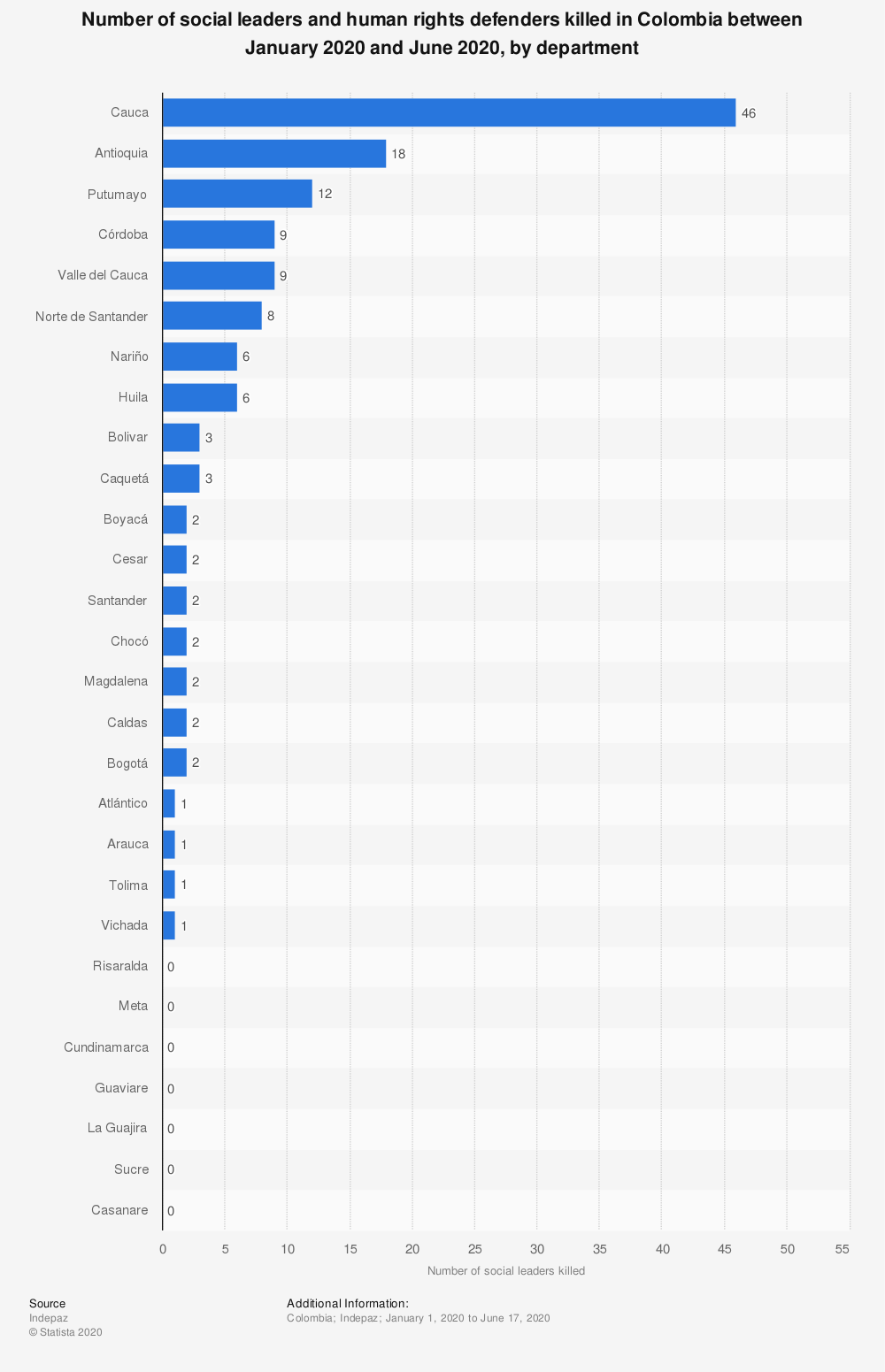

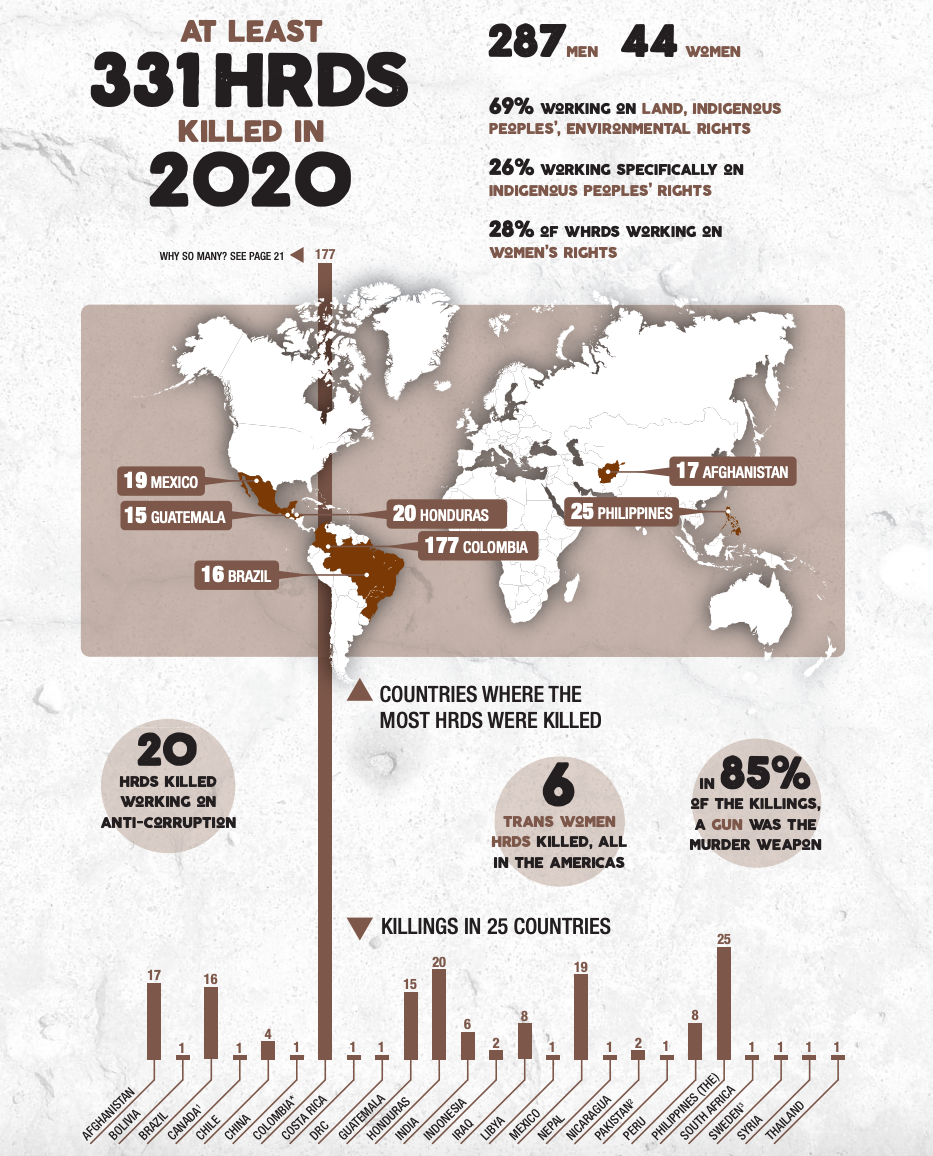

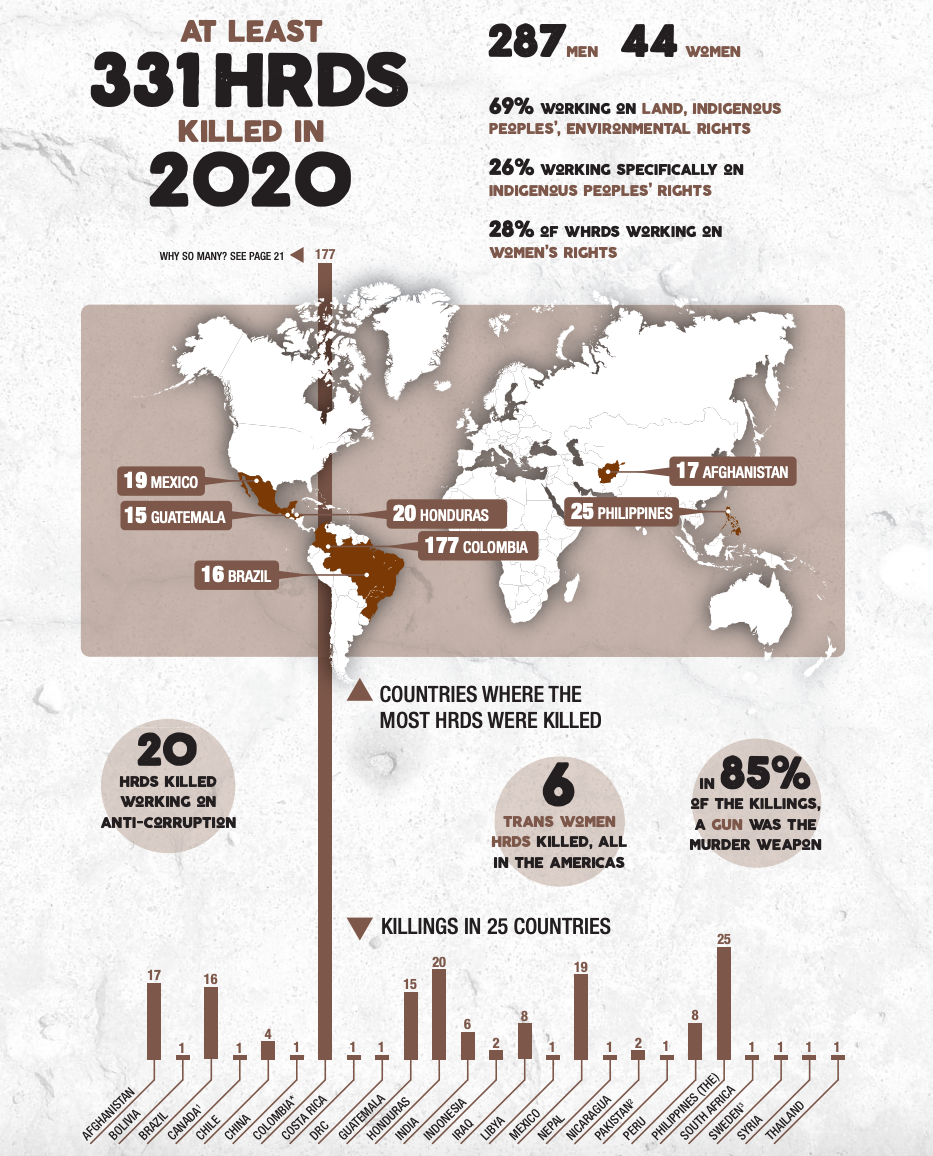

According to a recent report by non-profit Frontline Defenders, of the 331 people promoting social, environmental, racial, and gender justice killed in 2020, 177 were Colombian, with scores more beaten, detained, and criminalised because of their work.

Earlier this month, a separate analysis conducted by Human Rights Watch (HRW) criticised the Colombian government for their lack of action and failure to provide protection to activists.

With Latin America the most dangerous continent in the world, where crime rates are more than triple the global average, President Duque has received countless international demands that more be done to stop violence against social leaders (as they’re locally referred to in Colombia).

He did not, however, offer a timeline nor any alternative details about the expanded military operations.

Activism has long been a dangerous vocation in Colombia. From the right-wing paramilitary groups that murdered trade unionists, Communists, and locals between the 1980s and early 2000s, to present day -wherein, despite the 2016 peace accord aimed at improving conditions in rural areas controlled by illegal gangs, activists are still routinely targeted by armed groups.

Marta Hurtado, spokeswoman for the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights attributes this to a ‘vicious and endemic cycle of violence and impunity in Colombia.’