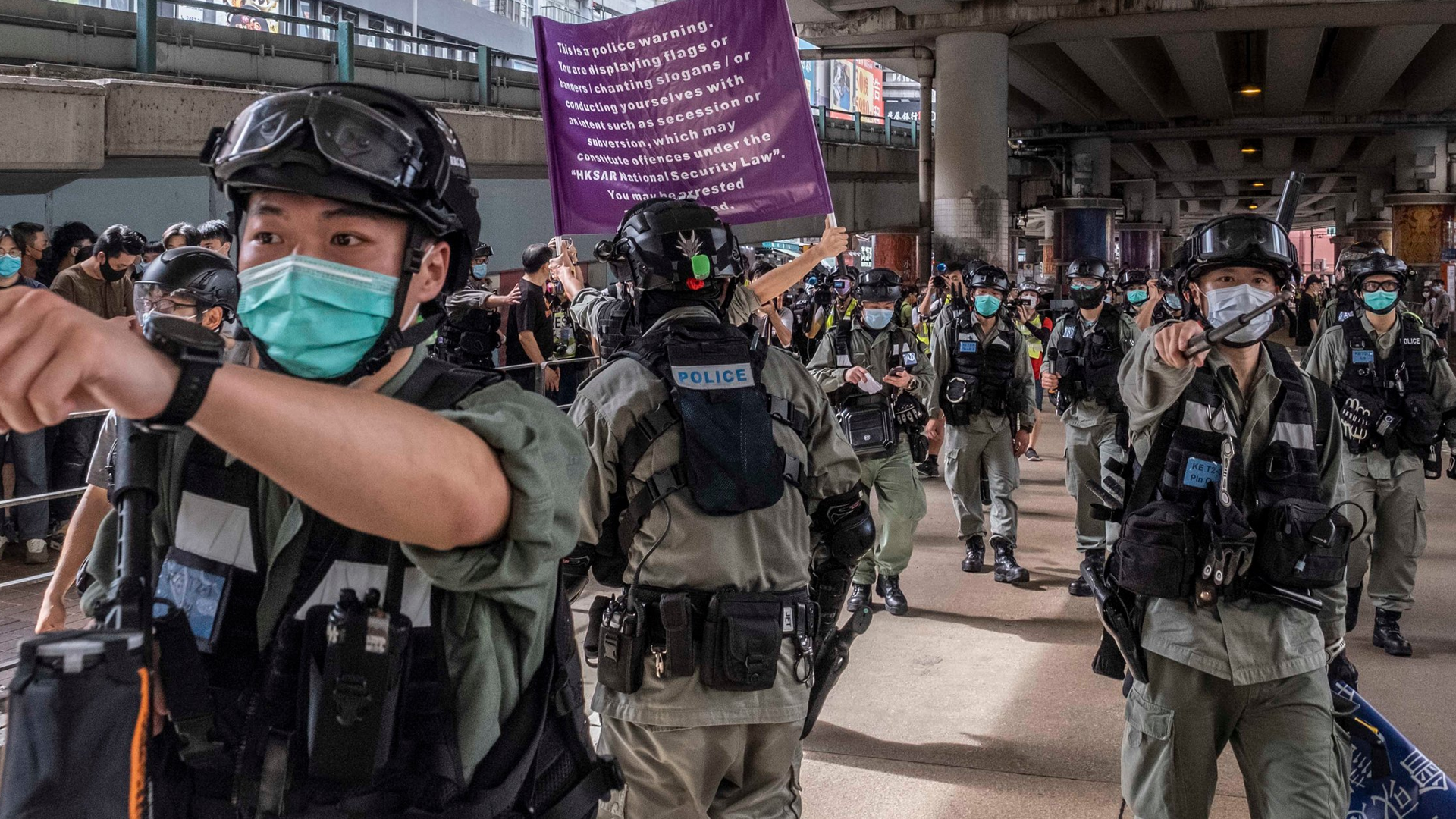

What is this new security law?

Put simply, China’s new regulations over Hong Kong allows the state to set up a national security agency that’s staffed by officials who don’t have to follow local laws.

There are several new rules with sever repercussions that come along with this. Damage to any vehicles or government equipment is strictly prohibited and will now be considered an ‘act of terrorism’. Individuals found to be ‘colluding with foreign forces’ will also be punished, though what is meant by ‘foreign forces’ is up for interpretation. Punishments for these security laws can include the suspension of any company operations, bans from all future Hong Kong elections, and life in prison. This can apply to anyone in the area, regardless of whether they’re a permanent citizen or not.

This could change Hong Kong’s legal system significantly as it ushers in new crimes with extreme punishments and gives Beijing excessive power over the region in a way that it hasn’t had before. The terms of the law are very vague and while officials have tried to reassure citizens that their rights and liberties are not at risk, the public are understandably unconvinced.

How is this law affecting people in Hong Kong?

This security law was obviously designed to break up protest efforts and disband large resistance groups. So far it seems to be working. Leading democracy campaigner Nathan Law has left Hong Kong fearing for his safety, and many public banners and phrases such as ‘Liberate Hong Kong’ have now been banned.

Social media channels and encrypted feeds that organise protester gatherings have gone silent since this new law passed, and there are no demonstrations planned for the next few days. International businesses are re-evaluating their presence in the region and local writers, activists, and protestors are having to clear up their digital footprints to make sure they don’t wind up in jail. According to The New York Times, over twelve writers have asked editors of pro-democracy site InMedia HK to take down their work – over 100 articles have now been removed.

There has been news of some potential resistance to these developments over the last day or so, however. The Guardian has written about a potential ‘parliament in exile’ that’s in the early stages of preparation which could send a clear message to Beijing and the state if it materialises. Campaigner Simon Cheng, who is now living in exile in Britain, has said activists are trying to ‘develop an alternative way to fight for democracy’ that doesn’t risk jail time but still makes clear that the Hong Kong people want change. This shadow parliament would presumably exist outside of Hong Kong, though in these early stages the logistics are still unclear.

How have nations around the world responded?

Unsurprisingly, many nations across the world have condemned China for this move. The US has just passed sanctions that will penalise banks that do business with China, though it has yet to be signed by Trump. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi stated that the security law is a ‘brutal, sweeping crackdown, intended to destroy the freedoms [the people] were promised’.

The UK has also spoken out, offering settlement for up to three million Hong Kong residents. Those affected are being offered a ‘route out’ as Prime Minister Boris Johnson put it yesterday, and can stay in the UK for up to five years, after which they can apply for citizenship.

China meanwhile has been very vocal about any interference from outside nations, warning of damaged relations and severe repercussions. The state just hired Zheng Yanxiong as chief of this new Hong Kong security agency, who’s known for his hard-line involvement with a 2011 protest over land dispute in southern China. The state is not backing down, essentially.

All of this could complicate international relations, particularly with the UK and US, who both frequently trade with China on a regular basis. The UK’s 5G network is being partly built by China’s own Huawei, for example, and it may need to rethink how this will work moving forward. It’s also a desperate time for protestors, who are having civil rights and liberties revoked rather than granted, which is the opposite of what they’ve been demanding for close to a year.

While feet on the ground and in the streets may be lighter in the coming months, protestors are not giving up – and the fight continues. Activism will have to adapt with these new rules, and a potential shadow parliament could help to get the message out. The good news is that China’s activity hasn’t gone unnoticed, and democratic countries are implementing deterrents to halt the state from going further. Hopefully even more will be done to protect those in Hong Kong in the future.

For now we’ll have to see what happens, but this is far from over.